The Dilemma of Professional Skepticism: A Critical Examination

Written on

In the words of Lady Macbeth, “’Tis safer to be that which we destroy, than by destruction dwell in doubtful joy.” This sentiment underscores the challenges within the realm of professional skepticism, particularly as it pertains to extraordinary claims, a principle famously articulated by sociologist Marcello Truzzi, who identified as a "constructive skeptic" of paranormal phenomena.

In the mid-1970s, Truzzi articulated a key tenet that would later be popularized by astronomer Carl Sagan: “An extraordinary claim requires extraordinary proof.” This notion, later dubbed the “Sagan standard,” was reiterated by Sagan in 1980 as “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” Truzzi, however, grew disillusioned with the organization he co-founded, the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), now known as the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI). He resigned approximately a year after its inception, citing a shift towards what he termed “pseudo-skepticism,” where members seemed more interested in attacking claimants than conducting genuine investigations.

Truzzi lamented being criticized by committee members for being "too soft" on those making paranormal claims, emphasizing that his approach was to engage with the best proponents in the field, asking for their strongest evidence. He observed that the organization's focus had shifted away from inquiry and towards advocacy for scientific orthodoxy.

This situation, as Truzzi pointed out, has not improved over time. In my own writings, particularly in "Daydream Believer" (2022), I have highlighted an intellectual crisis within professional skepticism, wherein self-proclaimed rationalists often misinterpret or distort the truth in what they perceive to be a defense of rationalism.

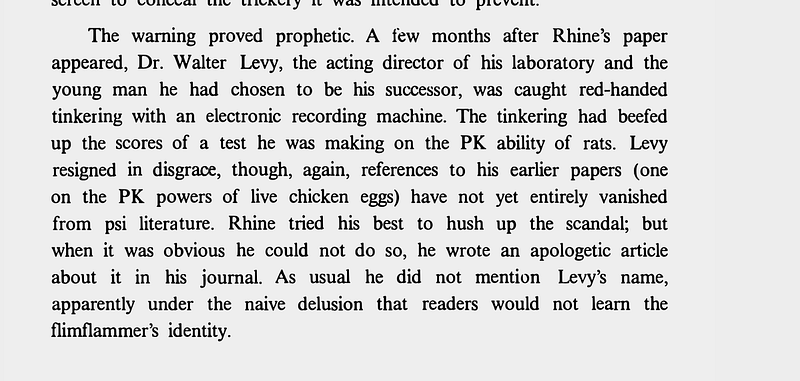

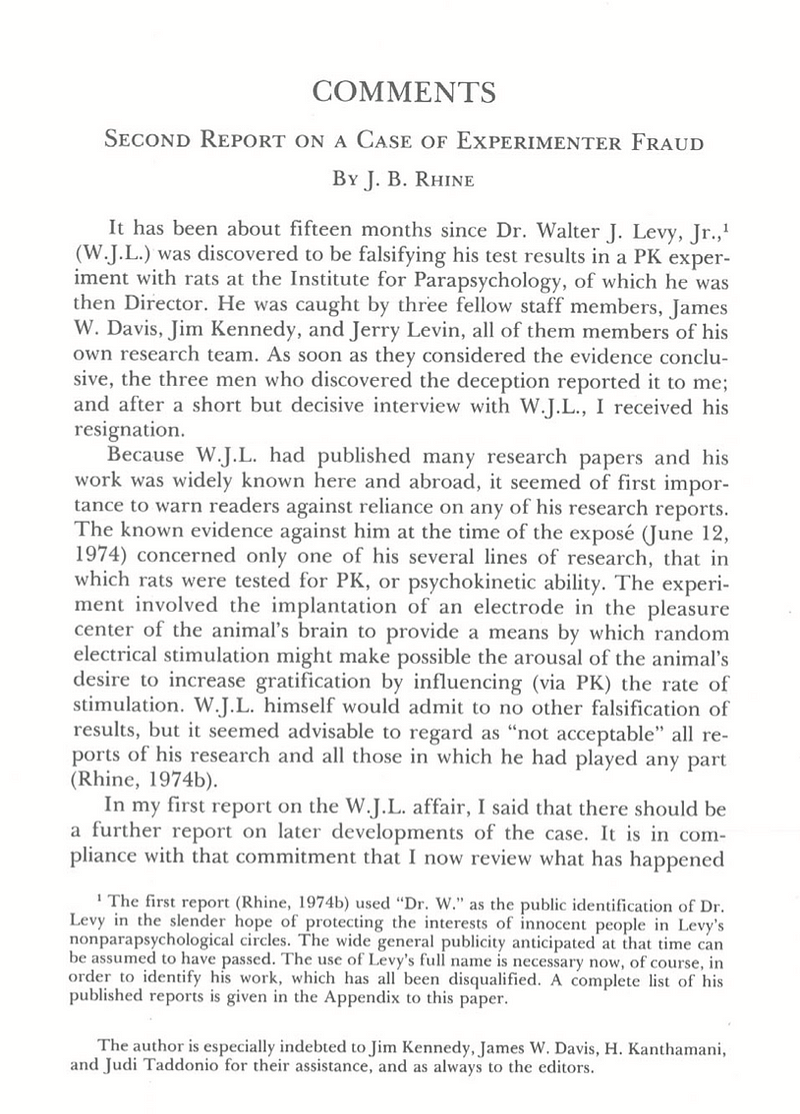

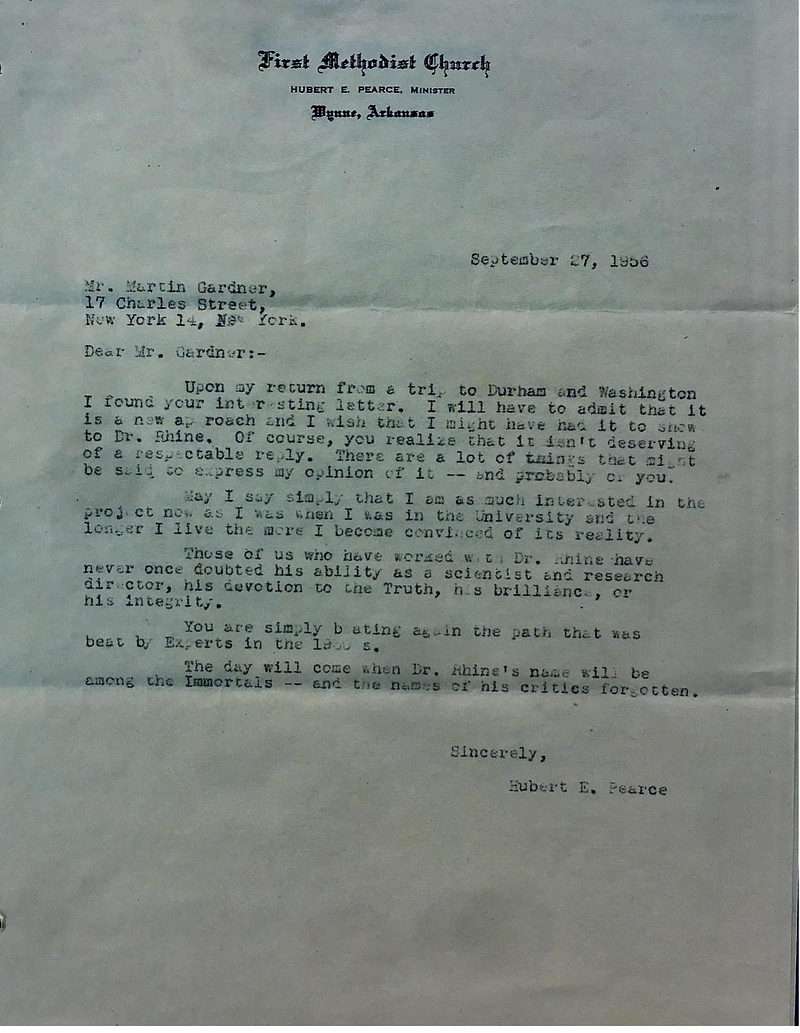

A pertinent example can be found in Martin Gardner's "On The Wild Side" (1992), where he critiques parapsychologist J.B. Rhine, a key figure in the field. Gardner's opening chapter, “The Obligation to Disclose Fraud,” criticizes Rhine for not disclosing a significant cheating incident in his ESP lab during the 1970s. Gardner claimed that Rhine attempted to suppress the scandal but later penned an article acknowledging it without naming the perpetrator, under the assumption that the public would remain unaware of the identity of the fraudster.

Gardner's portrayal of Rhine’s actions was misleading. Rhine had indeed written two articles addressing the cheating scandal in detail, one of which explicitly identified the cheater. He stated that any reader could easily find out the individual’s name if they wished, asserting his intent was not to conceal the truth but to maintain respect for personal rights.

Despite Gardner's narrative, Rhine’s commitment to transparency was evident. In contrast, Gardner’s claims lacked proper sourcing, relying instead on unverified assertions. This pattern of skepticism often manifests itself within the broader discourse surrounding parapsychology.

As a significant figure in the skeptical movement, Gardner was not alone in his approach. His standards reflect a troubling trend within professional skepticism, illustrated by the actions of other notable skeptics, such as James Randi. This issue extends beyond individual disputes, as seen in Richard Feynman's famous “Cargo Cult Science” address, where he criticized the embrace of confirmation bias rather than the rigorous testing of hypotheses.

In a noteworthy incident in 1979, physicist John Archibald Wheeler inaccurately accused Rhine of fraud during a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Although he later retracted his statement, it exemplified the persistent issues surrounding the intersection of skepticism and parapsychology.

Recent analyses of Rhine’s ESP experiments have shown that a significant proportion of independent replications yielded statistically significant results, challenging the narratives often circulated by skeptics. In discussions about the state of skepticism today, it is clear that misrepresentations can become entrenched in academic and public discourse, often perpetuated through platforms like Wikipedia.

Ultimately, the professional skepticism field requires a new generation of skeptics who genuinely uphold rigorous standards of inquiry. As someone who identifies as a critical yet believing historian of the occult, I recognize the necessity of transparency and ethical practices within skepticism. There is a pressing need to cultivate an environment in which constructive criticism prevails over cynicism, ensuring that both parapsychology and science can flourish.