Nuclear Bombs and Their Surprising Link to Obesity Insights

Written on

Chapter 1: The Unforeseen Experiments of Nuclear Testing

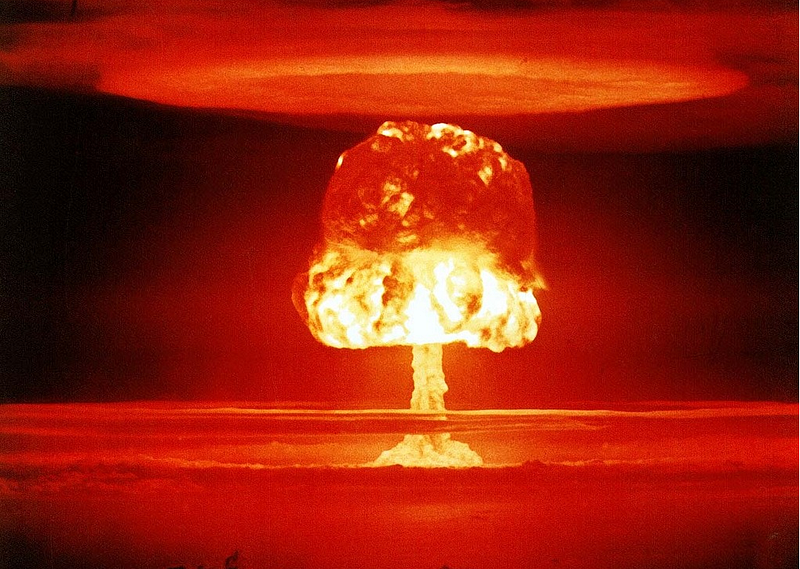

The vivid flash of a nuclear explosion is so intense that it makes you aware of your very bones, even with your eyes shut. The subsequent heat is described as if a person of similar size had ignited and walked through you. Such is the profound impact of a nuclear bomb test.

Credit: Gerd Altmann/Pixabay

Between 1955 and 1963, the United States and the Soviet Union conducted numerous explosive tests, creating massive fireballs that shook the earth. Following this period, nuclear tests transitioned underground and eventually ceased. However, the military observers at the time were unaware that they had inadvertently initiated two significant experiments. Not only were they assessing the destructive capacity of their weapons, but they also marked the entire human population with radioactive signatures. Years later, these atomic tests would offer new perspectives on brain development, healing processes, and obesity.

Section 1.1: Understanding Fallout

The scientists orchestrating the atomic bomb tests concentrated extensively on the energy released during the explosions. They gave considerably less thought to the fallout — the radioactive dust flung into the upper atmosphere. Unlike the ash from a conventional fire, fallout behaves differently. The extreme heat of a nuclear explosion converts materials into minuscule particles, with a single fallout particle being hundreds of times smaller than a blood cell. Due to their small size and lightness, these particles can remain airborne for years, eventually settling anywhere across the globe.

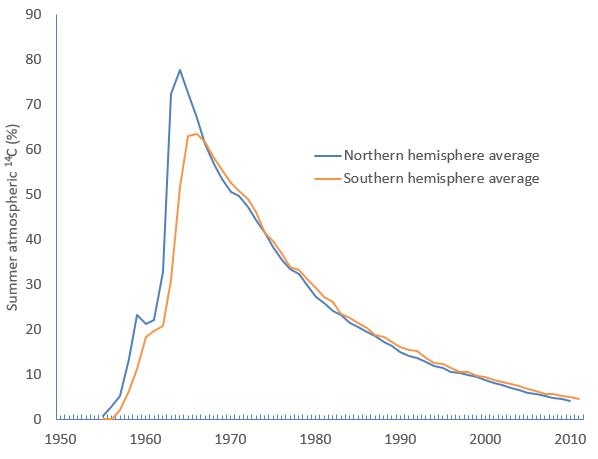

During the nuclear testing era, fallout enveloped the planet. Monitoring stations in both hemispheres recorded elevated levels of radioactive carbon in the atmosphere, peaking in the mid-1960s and nearly doubling the natural amount. This excess lingered for decades, slowly diminishing.

Credit: Mike Christie/Wikipedia

Once fallout settles, it is absorbed by plants, which are then consumed by humans or animals. This radioactive carbon ultimately finds its way into our bodies. Carbon is crucial for life, and our bodies utilize it to construct every cell, from skin to muscle. When your body generates cells, it uses whatever carbon is available, which may include both radioactive carbon-14 and regular carbon-12. While the majority of carbon in our bodies is carbon-12, the proportion of carbon-14 notably increased during the 1950s due to nuclear testing.

Scientists excel at measuring the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12, a technique also employed to date ancient artifacts. By analyzing the carbon-14 levels in human cells, researchers can determine if a cell was formed before, during, or after the nuclear test era. Essentially, the Cold War left a "manufactured on" date stamped on every cell in every person, leading to a new exploration of fat cells.

Subsection 1.1.1: The Nature of Fat Cells

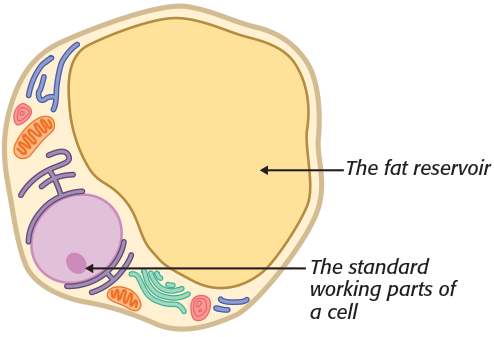

Every human body contains billions of fat cells, each acting as a tiny reservoir for fat. Under microscopic examination, fat cells are primarily composed of a droplet of fat.

Credit: Matthew MacDonald/”Your Body: The Missing Manual”

Researchers have determined that some individuals possess a greater number of fat cells than others. However, prior to the carbon-14 study, the lifespan of these fat cells remained a mystery. Were we born with a fixed number of fat cells, or do they die and multiply over time? To uncover this, scientists sought out carbon-14 in fat samples collected mainly from liposuction procedures. By measuring carbon-14 levels, they could assess the average age of fat cells.

The findings suggest that the body meticulously regulates fat. Regardless of whether a person is overweight or underweight, their body maintains a consistent number of fat cells. For instance, patients undergoing bariatric surgery typically lose substantial weight but retain the same number of fat cells. Similarly, if someone gains weight, their existing fat cells expand rather than multiply. Researchers suspect that although prolonged weight gain may eventually lead to new fat cell creation, this has yet to be confirmed.

Section 1.2: The Enigma of Fat Cell Quantity

The carbon-14 fat-cell study raises an important question: What determines the number of fat cells a person has? It is known that obese adults possess more fat cells than their lean counterparts, indicating that some factor informs the body on how many fat cells to generate, influencing whether a person is thin or overweight.

While the answer remains elusive, it may lie in childhood. Studies indicate that children accumulate fat cells as they grow, and those who are obese from a young age tend to have a higher number of fat cells, increasing their risk for obesity in adulthood. It appears that overeating during childhood may lead to a higher fat cell count into adulthood, potentially resulting in lifelong weight challenges. However, the full explanation is likely multifaceted, involving genetics, childhood weight gain, and environmental influences that shape a developing body for adult obesity. If this process occurs in childhood, it presents a critical opportunity for intervention.

Interestingly, the common approach of fat removal through procedures like liposuction does not seem effective. Not only is fat removal risky, but it rarely results in lasting weight loss. Studies indicate that individuals who undergo liposuction tend to regain fat within a year, often redistributing it to different body areas. It remains uncertain whether the body compensates by accumulating more fat in fewer cells or by increasing fat cell production to restore the original count.

Researchers continue to delve into the complexities of fat. They have also utilized carbon-14 to investigate how the body forms various tissues, from brain neurons to foot tendons. However, the effects of Cold War-era radioactive fallout are diminishing, with predictions that by 2050, its impact may vanish completely. Cleaner air and less radioactive flora will mean the loss of a valuable opportunity to further understand the inner workings of our bodies.

Chapter 2: The Future of Research on Fat Cells

Enjoyed this read? Check out the other articles in my Science of Eating series:

- Is long-term weight loss out of reach for most people?

- The Calorie Myth: Debunking the worst bit of nutrition science

- Why your body wants to be fat: Anti-starvation system, meet the modern world