High-Protein Diets: Unpacking the Link to Atherosclerosis

Written on

The Macronutrient Debate

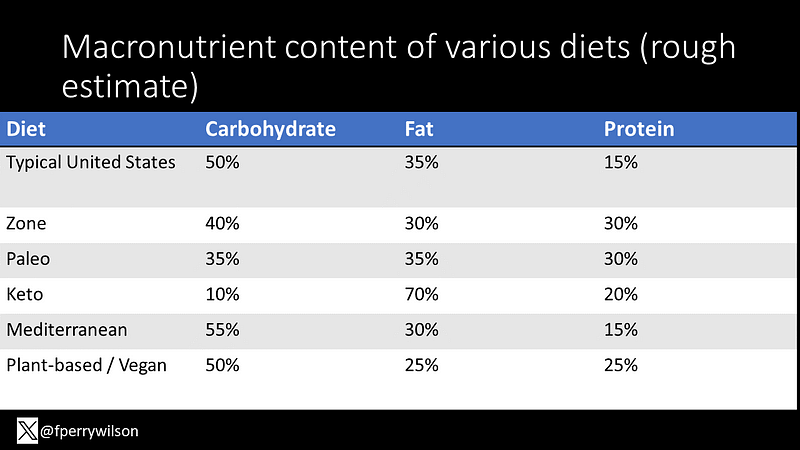

Dietary macronutrients—fat, carbohydrates, and protein—are fundamental to our energy needs and have been central to dietary discussions for decades. Since the late 1980s, trends have swung from low-fat diets, which suggested that "fat makes you fat," to the 90s and early 2000s, where the focus shifted to reducing carbohydrate intake, particularly sugars. Today, protein is capturing the spotlight.

The Rise of Protein-Centric Diets

High-protein diets like the Paleo and Zone diets have become increasingly popular. The keto diet, while primarily anti-carbohydrate, also elevates protein intake due to its nature of restricting other macronutrients. This shift has led to rising protein consumption across various diets.

The Health Implications of Protein

It seems logical that high-protein diets are beneficial; after all, muscles and other crucial bodily components are made from protein. However, research does not consistently support the notion that high-protein diets are particularly healthy. Animal studies often indicate a link between higher protein intake and increased atherosclerosis. Some epidemiological research in humans also suggests a correlation between protein consumption and heart disease.

Is There a Risk?

A recent study proposes that the adverse effects associated with protein intake may be attributed to a specific amino acid—leucine. The research, published in Nature Metabolism by Xiangyu Zhang and colleagues from the University of Pittsburgh, merits closer examination.

Understanding the Study

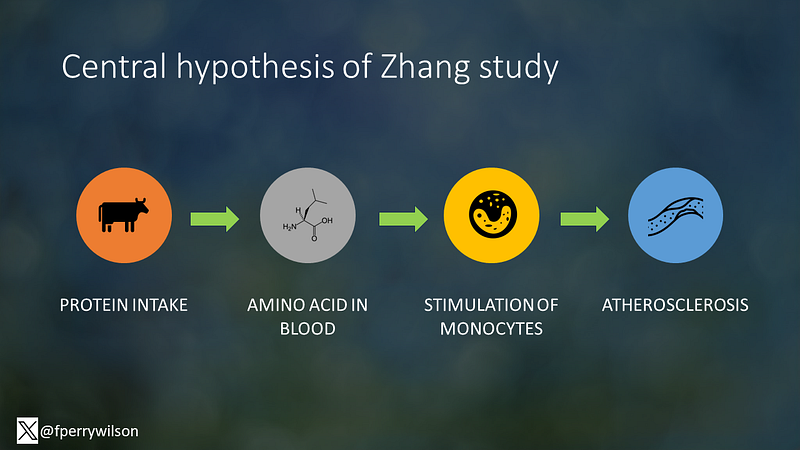

The researchers hypothesized that protein consumption elevates amino acid levels in the bloodstream, which in turn activates inflammatory cells known as monocytes. This inflammation could potentially lead to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular issues.

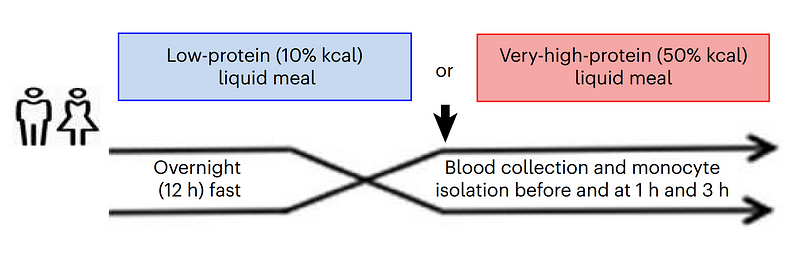

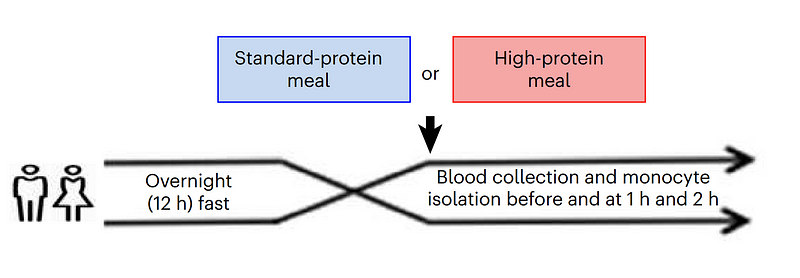

The study involved two tightly controlled human experiments. In one, 14 participants fasted for 12 hours before consuming either a low-protein or high-protein shake, with blood samples taken afterward to measure amino acid levels.

A second experiment followed a similar design, but participants consumed solid meals with different protein content—15% versus 22%.

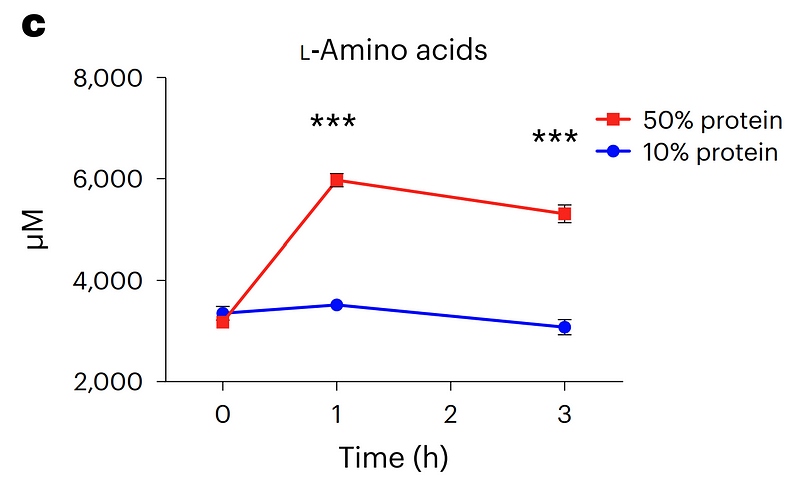

Results showed that protein intake indeed increased amino acid levels in the blood, confirming the efficiency of digestion.

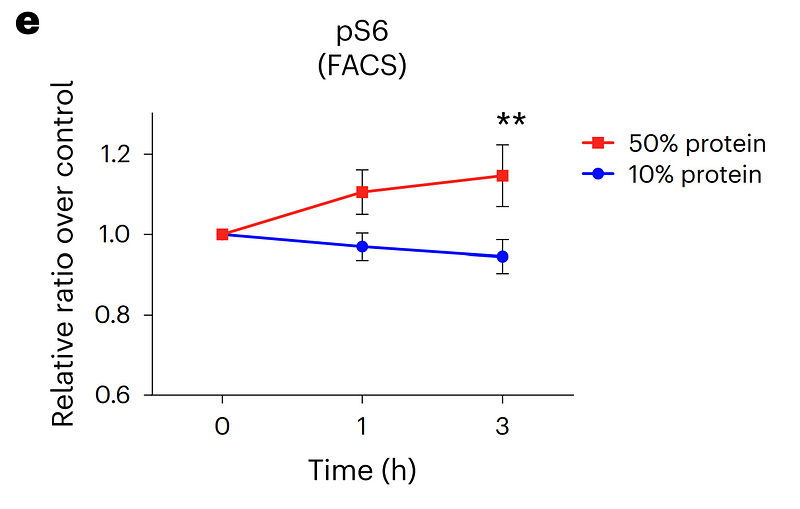

More intriguingly, the study analyzed monocyte activation, revealing approximately 20% greater activation post high-protein intake.

Identifying the Culprit Amino Acid

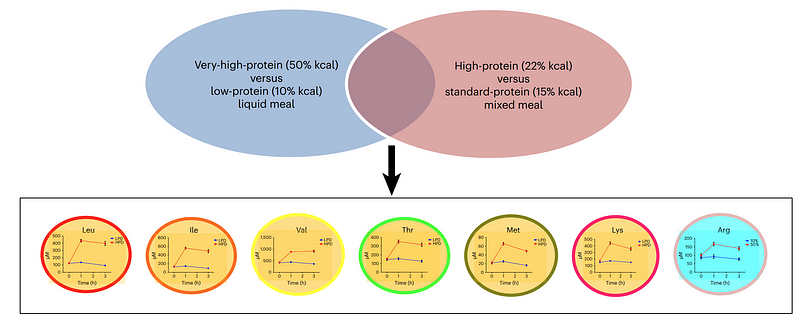

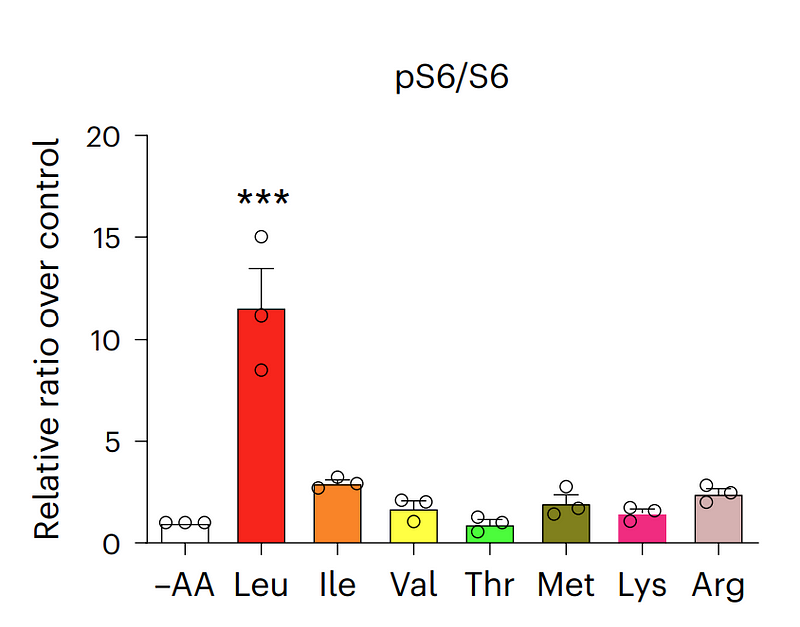

The researchers aimed to pinpoint which amino acid was responsible for the increased inflammation. They narrowed their focus to seven candidates that were elevated in both experiments. They then tested these amino acids on cultured monocytes to see which ones stimulated the cells most effectively. The frontrunner? Leucine.

Leucine is one of three branched-chain amino acids and is essential, meaning we must obtain it from our diet. It's abundant in protein-rich foods, particularly animal proteins.

Normal doses of leucine were then tested on monocytes, showing a clear dose-dependent increase in activation.

The Bigger Picture: The Protein Paradox

This study offers a compelling perspective on the so-called "protein paradox." If high-fat, high-carb, and high-protein diets all carry potential risks, what should we eat? While this may humorously suggest avoiding all macronutrients, it highlights the importance of a balanced diet.

Calories matter: the study controlled for total caloric intake, which may not reflect real-world eating habits. A high-protein diet could lead to lower overall calorie consumption, potentially offsetting any negative effects from increased leucine.

For those concerned about protein, it’s noteworthy that leucine is predominantly found in animal sources. Therefore, if you prefer a protein-rich diet, considering plant-based protein sources might be a healthier option.

Bon appétit.

This video discusses how high-protein diets might contribute to atherosclerosis, highlighting the role of leucine.

This video covers a study from the University of Missouri that shows excessive protein intake can be harmful to health.