The Unmatched Sound of Krakatoa: A Volcanic Catastrophe

Written on

Chapter 1: The Eruption's Soundwave

On August 27, 1883, an explosion occurred that surpassed any noise previously recorded on Earth. It was 10:02 a.m. when the island of Krakatoa, located between Java and Sumatra in Indonesia, released a thunderous sound. This noise traveled an astonishing distance, being detected 1,300 miles away in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, 2,000 miles away in New Guinea, and even 3,000 miles away in Rodrigues, an island in the Indian Ocean. This remarkable auditory event was reported in over 50 locations, covering an area equivalent to a thirteenth of the globe.

Consider the enormity of this phenomenon. If you were in Boston and someone claimed to hear a sound from New York City, you might be skeptical, given that it's only 200 miles apart. Now, imagine being in Boston and clearly hearing a noise from Dublin, Ireland. Traveling at the speed of sound (approximately 766 miles or 1,233 kilometers per hour), it would take about four hours for that sound to reach you. This explosion represents the farthest sound ever documented in human history.

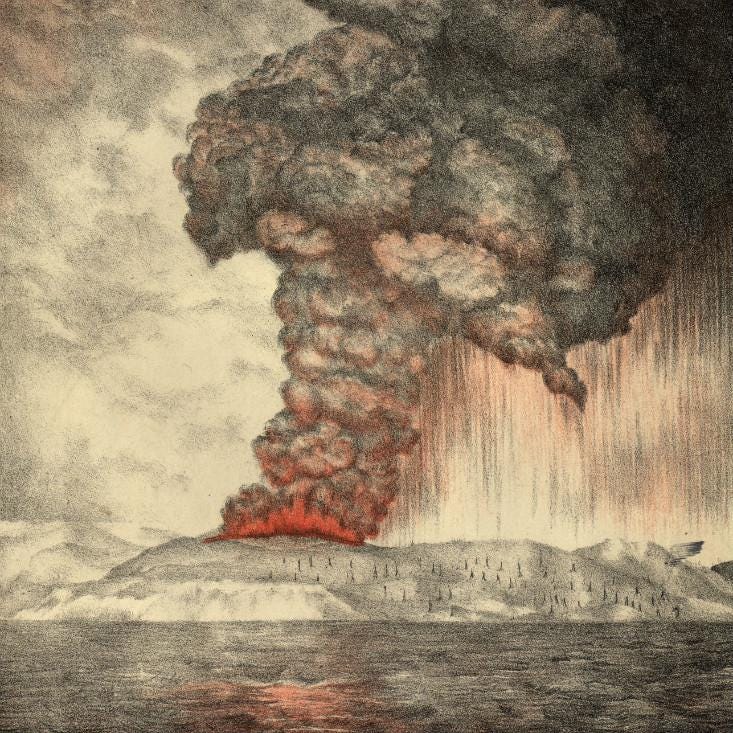

What could generate such an overwhelming noise? The eruption of Krakatoa was so intense that it shattered the island, sending a plume of ash soaring 17 miles into the sky, as noted by a geologist who witnessed it. This eruption propelled debris at speeds exceeding 1,600 miles per hour—more than twice the speed of sound.

This cataclysm also triggered a tsunami with waves over 100 feet (30 meters) tall, obliterating 165 coastal villages. The death toll was estimated by Dutch authorities at 36,417, but some estimates soar above 120,000.

The British vessel Norham Castle was situated 40 miles from Krakatoa when the explosion occurred. The captain documented in his log, “The explosions were so violent that over half my crew suffered ruptured eardrums. I fear this is the Day of Judgment.”

Fundamentally, sounds arise from fluctuations in air pressure. A barometer located at the Batavia gasworks, about 100 miles from Krakatoa, recorded a pressure spike exceeding 2.5 inches of mercury—equating to over 172 decibels of sound pressure. For context, the noise generated by a jackhammer measures around 100 decibels, while the threshold of pain for humans is approximately 130 decibels. Standing near a jet engine, one would experience a sound level around 150 decibels. The Krakatoa eruption's 172 decibels at a distance of 100 miles is astonishingly near the upper limit of what we classify as "sound."

When you vocalize or hum, you create pressure variations in the air. The louder the sound, the more significant these variations. However, there's a maximum limit to sound intensity. Exceeding this limit generates shock waves, as the fluctuations cause low-pressure areas to reach zero pressure—creating a vacuum.

Closer to Krakatoa, the sound exceeded this threshold, resulting in a powerful blast of high-pressure air that ruptured sailors' eardrums even 40 miles away. As the sound wave traveled thousands of miles, it transformed into a distant rumble. Over 3,000 miles from the source, the pressure wave faded to inaudibility but continued to propagate for days, resonating around the world.

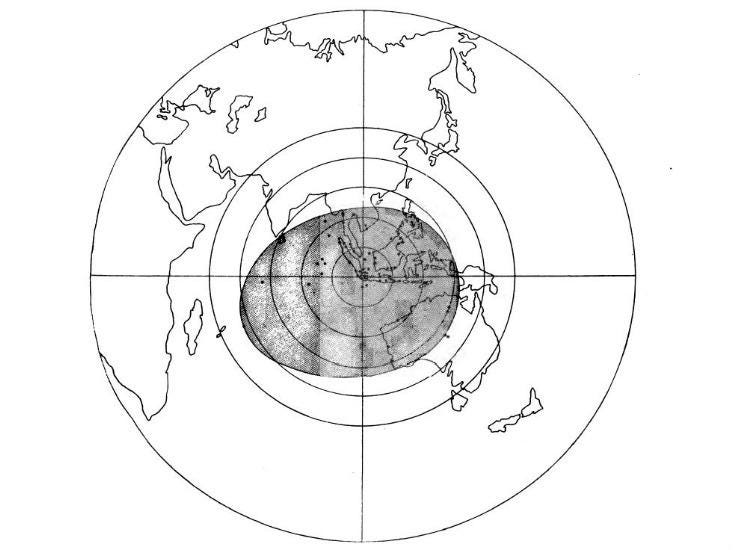

Six hours and 47 minutes post-eruption, a pressure spike was detected in Calcutta. Within eight hours, this pulse reached Mauritius and Australia. Cities like St. Petersburg, Vienna, and Paris noted the pressure surge within 12 hours, while New York, Washington D.C., and Toronto felt it 18 hours later. Remarkably, weather stations in 50 cities observed this unprecedented pressure spike for up to five days, occurring approximately every 34 hours—roughly the time it takes for sound to encircle the Earth.

The pressure waves from Krakatoa completed three to four circuits around the globe, with cities experiencing multiple spikes. Simultaneously, tidal stations in India, England, and San Francisco recorded increases in ocean waves, an occurrence previously unseen. This sound, though inaudible, traveled the world, earning the moniker “the great air-wave.”

The first video titled "The Loudest Natural Sound on Earth: The Krakatoa Volcanic Eruption" offers insight into this cataclysmic event, showcasing its historical significance.

Recently, a captivating home video captured a volcanic eruption in Papua New Guinea, demonstrating the pressure wave it created.

As the volcano erupted, it generated a sudden spike in air pressure, visibly condensing water vapor into clouds. The videographers were fortunate to be at a safe distance, as the pressure wave reached them approximately 13 seconds after the explosion, producing a sound akin to a massive gunshot. Calculating the distance using the speed of sound suggests that they were about 4.4 kilometers (2.7 miles) from the eruption site. Unlike this localized event, the Krakatoa explosion's roar reached as far as 3,000 miles away, illustrating nature's extraordinary and destructive power.

References

- Judd, J.W., et al. The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena. Trübner & Company, (1888).

- Winchester, S. Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded. Penguin, London, United Kingdom (2004).

- Simkin, T. & Fiske, R.S. Krakatau, 1883, the Volcanic Eruption and Its Effects. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, Washington, D.C. (1983).

Aatish Bhatia is a physics Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University, aiming to make science and engineering more accessible. He authors the acclaimed science blog Empirical Zeal and can be found on Twitter as @aatishb.

Thanks to Nicole Sharp and Will Slaton for their valuable insights regarding the physics of the Krakatoa explosion.