The Hot Hand Fallacy: Exploring a Controversial Phenomenon

Written on

The Concept of the Hot Hand

The hot hand fallacy is a topic that has sparked debates among both the general public and academics alike. This essay aims to delve into the scientific aspects of this intriguing concept. In recent decades, the field has seen significant developments.

To kick things off, I will provide a brief overview of the hot hand concept. Next, I will discuss the historical research that has stirred the scientific community. Finally, we will examine the latest studies that have redefined our understanding of this phenomenon. Let's embark on this journey with the hope of grounding our insights rather than complicating them further.

What Exactly is the Hot Hand?

During my childhood, I often played cricket with my friends. For those unfamiliar, cricket involves a bat, a ball, and two teams of eleven players each—this basic understanding will suffice for our discussion.

I was not particularly skilled at cricket, nor was I held in high regard by my peers. However, one day, I found myself in an extraordinary zone. I was hitting the ball with precision, and my coordination was impeccable.

Facing a formidable bowler from the opposing team, I managed to hit two consecutive balls perfectly, one of which soared out of the park! Our team captain rushed over to my teammate at the other end, exclaiming with enthusiasm:

"We need to ensure Hemanth faces as many balls as possible! I've never seen him play like this before. Let's capitalize on his momentum while he's in the zone!"

I was both surprised and intrigued by this. At that moment, I felt an extraordinary force within me; I was performing like a top player, despite usually being one of the weaker ones. This experience exemplified what we refer to as the hot hand, and it seemed everyone around me sensed it.

Many people have had similar moments of unexpected excellence, whether in sports or even academic tests. The concept of the hot hand is something most people intuitively grasp or have experienced firsthand.

The Hot Hand Fallacy Explained

In 1985, researchers Thomas Gilovich, Robert Vallone, and Amos Tversky published a pivotal paper titled "The hot hand in basketball: On the misperception of random sequences." This research focused on basketball and posited that the hot hand phenomenon was a fallacy.

Amos Tversky, a renowned figure in behavioral psychology, was among the co-authors. His collaborator, Daniel Kahneman, later won the Nobel Prize for their joint work in behavioral psychology. Had Tversky been alive at that time, he would have likely shared in that recognition.

Tversky's legacy is well-established in the social sciences, particularly for his contributions to understanding human biases and fallacies. It’s no surprise that their research generated considerable discussion and debate, as it appeared methodologically sound.

Investigating the Hot Hand Fallacy

Gilovich and his colleagues analyzed basketball shooting statistics from the Philadelphia 76ers during the 1980-81 season, free throw records from the Boston Celtics, and a controlled experiment involving Cornell's varsity teams. Their goal was to determine whether players' hot streaks were statistically different from random occurrences.

In simpler terms, they sought statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis, which stated that the hot hand does not exist. For those interested in a deeper dive into statistical significance, I recommend my essay: "How to Really Understand Statistical Significance?"

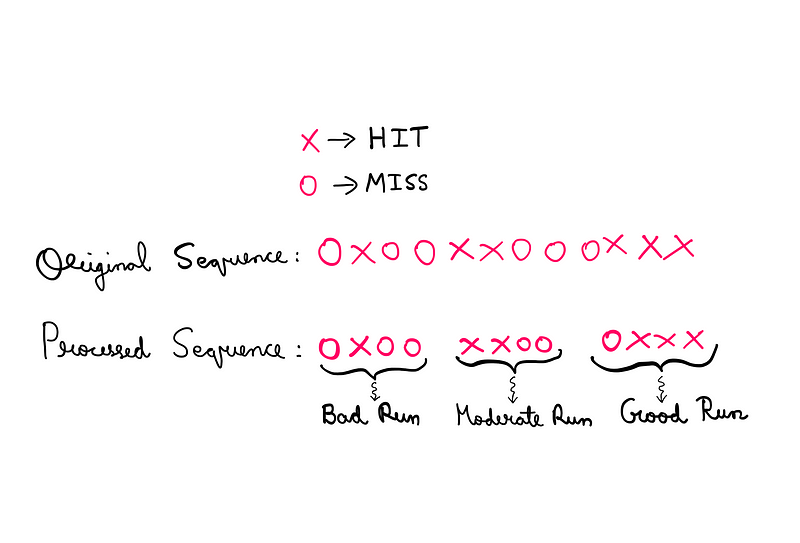

The researchers divided shooting sequences into blocks of four attempts, categorizing them as poor (0 or 1 hits), moderate (2 hits), or good (3 or 4 hits).

For a player with a 50% success rate, assuming the null hypothesis holds true, these combinations should be equally likely. Specifically, you would expect 31.25% of the sequences to be poor, 37.5% to be moderate, and 31.25% to be good.

Gilovich and his team then posed a crucial question: If the null hypothesis is valid, how unlikely is it that we observe the results we see? The answer was a resounding "not very" (indicating no statistical significance). Consequently, they concluded that the hot hand was merely a cognitive illusion.

Their findings suggested that players who believed in the hot hand might make suboptimal decisions by favoring a hot player over a more skilled teammate.

“…the belief in the ‘hot hand’ is not just mistaken, it could also be costly.” - Gilovich et al.

The Aftermath of the Hot Hand Fallacy

Following the publication of Gilovich et al.'s work, the academic community erupted in intense discussions and debates. Tversky defended their methodology and highlighted flaws in the arguments of critics.

Years later, in 2015, Joshua Miller and Adam Sanjurjo released a paper titled "Surprised by the Gambler’s and Hot Hand Fallacies? A Truth in the Law of Small Numbers." This paper gained recognition for identifying significant flaws in Gilovich et al.'s original methods.

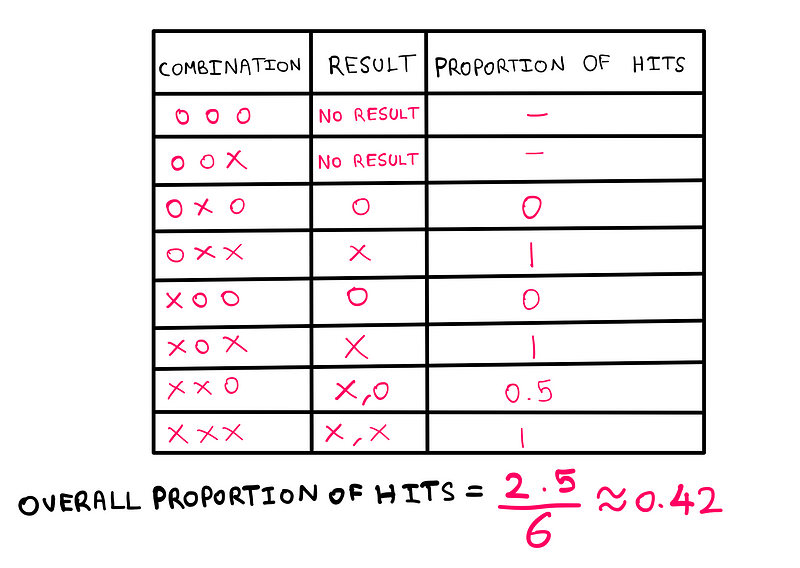

Miller and Sanjurjo pointed out that the practice of segmenting extensive data into blocks of four shots created a bias. To illustrate, let's consider predicting outcomes after each hit in sequences of three shots. Using a binomial model with a 50% chance of hitting or missing, we would identify eight possible outcomes.

By analyzing the immediate results after each hit and calculating the hit proportions for each sequence, we would expect a hit rate of 0.5. However, the table above shows a rate below 0.5.

Gilovich et al. employed four-shot blocks, and when we apply this logic, we also find a rate nearing 0.4. Thus, segmenting long sequences into blocks of four skews the data towards misses.

After correcting for this bias, Miller and Sanjurjo found that the data from Gilovich et al. indeed supported the existence of the hot hand, demonstrating statistical significance.

Moreover, Kevin Korb and Michael Stillwell, in their 2003 paper, argued that the statistical methods used by Gilovich et al. lacked the necessary resolution to detect statistical significance.

The Ongoing Debate Over the Hot Hand Phenomenon

Currently, the discourse surrounding the hot hand fallacy continues to evolve. Researchers are gathering more data and seeking to establish statistical significance, with mixed results emerging.

There is a growing focus on defining the phenomenon with greater precision. Some scholars argue that it’s not just about the number of hits, but also the speed at which they occur, complicating data collection efforts.

Ironically, Tversky fell into the same trap he and Kahneman frequently warned against: expecting smaller data sets to behave like larger ones, effectively applying the law of large numbers to limited data.

Richard Guy humorously critiqued this issue in a published paper. For those interested in further exploration, check out my essay on the strong law of small numbers.

To conclude, this narrative highlights the fundamental challenges within statistical research, particularly concerning the definitions of the null hypothesis and the interpretation of "statistical significance."

Epilogue

Reflecting on my childhood story of the hot hand, I remember sensing the tension from the opposing team as I prepared for the next ball.

With confidence, I executed a perfectly timed flick, only to witness the opposing keeper perform an astonishing dive to secure the catch. In disbelief, I walked off the field, my hot hand streak abruptly ending. That day, 'regression to the mean' claimed another victim.

References: Gilovich et al. (scientific paper), J. Miller and A. Sanjurjo (scientific paper), and K. Korb and M. Stillwell (scientific paper), and Jordon Ellenberg.

Further reading: "How To Perfectly Predict Improbable Events?" and "The Bell Curve Performance Review System Is Actually Flawed."

If you'd like to support my work as an author, consider contributing on Patreon.

This first video, titled "Is the 'hot hand' real? - Numberphile," explores the psychological and mathematical aspects of the hot hand phenomenon, providing insights into its validity.

The second video, "Do Past Shots Effect Future Shots (Hot Hand Fallacy)," discusses the implications of the hot hand fallacy in sports and decision-making contexts.