The Great Meteor Procession of 1913: An Unsolved Mystery

Written on

Chapter 1: A Celestial Spectacle

On February 9, 1913, a remarkable celestial event unfolded over Canada, leaving many puzzled about its true nature.

If you found yourself in Toronto that fateful night, you may have been fortunate enough to witness a stunning display in the sky. Shortly after 9 p.m., residents of the city gazed upwards to see numerous bright, comet-like entities moving in unison across the night sky.

What exactly did they observe? This occurrence, later named the Great Meteor Procession, was reported over an extensive area of about 10,000 kilometers, with Toronto being the focal point of sightings.

A meteor procession differs significantly from a typical meteor shower; it occurs when a meteor disintegrates upon entering the Earth's atmosphere, producing a series of fireballs traveling in the same direction. Such events are exceptionally rare, with only four recorded instances to date.

The primary documenter of this event, Professor Clarence Chant from the University of Toronto, did not witness the procession himself but was inundated with inquiries afterward. To satisfy public curiosity, he gathered eyewitness accounts and conducted a thorough investigation.

“An Extraordinary Meteoric Display”

In a paper he published in 1913 through the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Chant noted the varied and sometimes contradictory reports concerning the number and characteristics of the fireballs.

Some witnesses claimed to have seen only a handful of objects, while others reported hundreds or even thousands. Descriptions of the colors varied too, with some stating the orbs were red, while others saw them as yellow. The tails of these meteors were compared to searchlights, trails of sparks, or were said to be absent altogether. Additionally, some observers noted that loud rumbling sounds accompanied the sighting, intense enough to rattle windows.

Witnesses also remarked on the unusual slow speed and horizontal path of the meteors, a stark contrast to the expected rapid descent of shooting stars. The procession lasted for an extended period, with spectators estimating the duration to be anywhere from one to seven minutes, though the average was around 3.3 minutes—ample time for viewers to make a wish or two, as Chant humorously noted.

The meteor train was visible over an unprecedented distance, with sightings documented from as far away as western Alberta and a ship in the Atlantic near Brazil—a total stretch of approximately 9,600 kilometers.

In 2013, astronomers Don Olson and Steve Hutcheon uncovered additional historical maritime records, which revealed seven more ship sightings. This new information extended the known trajectory of the meteor procession by another 1,600 kilometers, raising questions about how these meteors could traverse such vast distances without crashing to Earth or disappearing into space.

Was it a natural phenomenon or something out of the ordinary?

Debate continues about what exactly lit up the skies over Toronto in 1913. Was it merely a meteor passing by Earth, or could it have been a mini-moon making its final orbit? While scientists generally agree that the Great Procession was a natural event, some, like Charles Fort, a chronicler of the unexplained, entertained the idea that it could have been orchestrated by an unknown intelligence.

In his 1923 work "New Lands," Fort pointed out the surprising lack of sightings in New York State, despite the established path of the procession. While weather conditions in the northeastern U.S. that night might explain the absence of reports, it raises the question of why nothing was seen in one of the most densely populated areas in North America.

Fort was known for chronicling bizarre occurrences rather than investigating them, often lacking a rigorous scientific approach. Nevertheless, the firsthand accounts suggest a deeper mystery. Chant noted that many witnesses likened the fireballs to a fleet of airships, meticulously organized in formation, a feat airmen of the time would struggle to achieve. Others compared them to large battleships with accompanying vessels, or even a brilliantly lit train seen from afar.

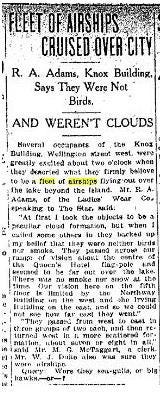

Airships Over Toronto?

Adding to the intrigue, the day after the meteor procession, observers in Toronto reported seeing what appeared to be a "fleet of airships" moving over the harbor, as detailed in the Toronto Star on February 10, 1913. Chant speculated that these might have been residual meteors, but this explanation seems improbable, as witnesses described the objects moving back and forth—behavior inconsistent with meteors.

Those interviewed by the Star were adamant that what they witnessed was neither clouds nor birds. While airships were indeed in existence during this time, they were primarily located in Europe, which was on the brink of World War I. The notion of a fleet of airships casually gliding over Toronto seems far-fetched, especially since photography was cumbersome at the time, resulting in no images of either the procession or the reported airships.

Could these "airships" have been the meteors making a second pass to survey the city during daylight?

In terms of likelihood, the meteor theory is significantly more plausible than an extraterrestrial explanation, although it lacks the same level of intrigue. Yet, many questions remain unanswered, and for those who believe, the Great Meteor Procession continues to be a captivating mystery yet to be unraveled.

The first video titled "The Great Meteor Procession of 1913" delves into this fascinating event, providing context and insights into what might have occurred that night.

The second video, "The Meteor Explainer," further explores the scientific aspects of meteors and their behaviors, shedding light on the phenomena witnessed during the Great Meteor Procession.