Exploring the Fascinating World of Firman and Its Historical Context

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Firman

In a lighthearted exploration of language, the term "firman" has garnered attention—not due to its association with a fictional superhero, but rather its rich historical significance.

Photo credit: Yusra Hussain, TNN

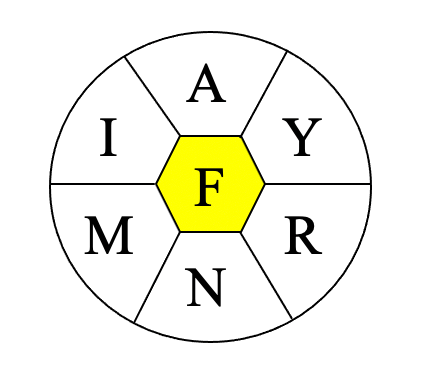

Recently, the New York Times Spelling Bee presented the letters A, I, M, N, R, Y, alongside a central F (all words must feature F). Merriam-Webster defines "firman" as follows:

Art by Iva Reztok

One might jest about the dictionary's authority: how could "firman" possibly be valid if the New York Times doesn't recognize it? For more intriguing insights, consider checking the Spelling Bee Master.

What’s the most fascinating word you've encountered in today’s puzzle?

My Perspective

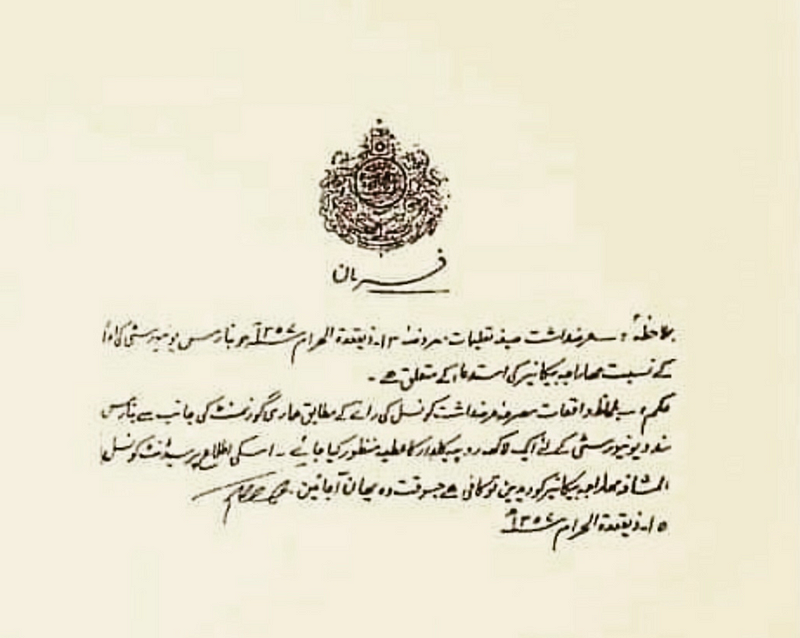

The image at the top of this section features a firman (also referred to as farman) authorized by the last Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan. This princely state was incorporated into India in 1948, shortly after the country gained independence. The firman he issued in 1939 allocated one lakh rupees to Banaras Hindu University, where "lakh" represents a hundred thousand in the Indian numbering system.

Royal Decree

According to Merriam-Webster, "firman" originates from the Turkish "ferman," which itself comes from the Persian "ferm?n," tracing back to Old Persian "fram?n." Admittedly, this etymology leaves much to be desired.

The 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica describes it as follows:

FIRMAN (an adaptation of the Persian "fermn," meaning mandate or patent, related to the Sanskrit "pram?na," signifying authority) refers to an edict from an oriental ruler, particularly pertaining to decrees, grants, and passports issued by the Sultan of Turkey, and signed by one of his ministers. A decree with the Sultan’s official signature, prepared with specific formalities, is termed a "hatti-sherif," which translates from Arabic to mean "noble command." Furthermore, a written decree from an Ottoman Sultan is identified as an "irade," deriving from the Arabic "ir?d," which means will or order.

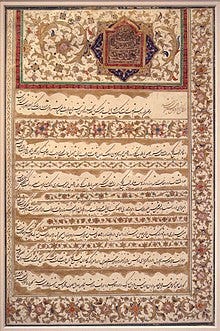

Many older firmans are exquisite pieces of art. Below is a firman signed in January 1831 by Fat’h Ali Shah Qajar, the second king of the Persian Empire during the Qajar dynasty.

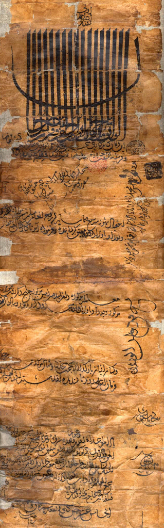

Additionally, here’s a firman signed by Taj ud-Din Firuz Shah (also known as Firuz Shah Bahmani), from around the early 15th century.

Photo credit: Feroz Shah Bahmani

Currently, a firman represents any written authorization provided by an Islamic official at various government levels. You might have heard of firmans as permissions for travel or approvals for scholarly research, including archaeological projects. They can be issued alongside different types of passports.

Fiiiiiiiiir–man!

The previous section evokes the exuberance of Birdman, the iconic 1960s Hanna-Barbera cartoon character who often called for help from his more adept purple eagle companion. For those unfamiliar with the character, you can find the introduction to Birdman here:

Chapter 2: The Legacy of Abbas ibn Firnas

Reflecting on my earlier commentary about Firman not being a Christmas tree superhero, there's indeed a historical figure named Firman who aspired to fly like a bird.

This individual was Abu al-Qasim Abbas ibn Firnas ibn Wirdas al-Takurini, or simply Abbas ibn Firnas. He lived during the 9th century in the Andalusian Caliphate of Córdoba, which today corresponds to modern-day Córdoba in Spain. This period marked a golden age for Islamic art and science, with Córdoba and Baghdad recognized as the cultural heartlands of the world known to Europe at the time.

Firman was a polymath, dedicating his life to various fields including invention, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, engineering, and even music and poetry. Notably, he developed a method for producing colorless glass, which was used to create magnifying lenses for reading.

Algerian historian Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari noted Firman’s adventurous spirit: among his many experiments, he attempted flight. Clad in feathers and equipped with wings, he leapt from a height, managing to glide for a significant distance. However, his landing resulted in injury because he overlooked how birds land—by using their tails.

I doubt al-Maqqari was implying that Firman literally needed a tail.

Photo credit: Zaltmatchbtw

Above is a statue commemorating Armen Firman, or Ibn Firnas, located outside Baghdad, Iraq.

Undeterred by his initial mishap, Firman constructed a glider and jumped from a tower, achieving a more successful flight. Unfortunately, he again landed poorly. Still no tail.

There’s some debate surrounding whether Firman and Ibn Firnas were indeed the same person or two distinct individuals. Some accounts suggest Firman performed the first flight, which Ibn Firnas witnessed as a child, later leading Ibn Firnas to create the glider. Others maintain that they were the same person whose feats were confused in historical accounts. Given that descriptions of Firman's wings sometimes resemble a "cloak with feathers" (similar to a glider), and both accounts end with unfortunate landings, I lean towards the theory that Firman and Ibn Firnas were indeed the same person.

Perhaps Firman was Ibn Firnas's superhero alter ego. Fiiiiiiiiir–man!

In 1976, a lunar crater on the far side of the Moon was named Ibn Firnas, honoring his pioneering work involving a series of rings that simulated planetary motions.

I told you he was remarkable!

Despite the stunning images of firmans and the contributions of Armen Firman, the editors of the Spelling Bee decided to classify "batt" as a non-word.

You can explore my previous entry discussing another non-word here:

Batt

The Spelling Bee insulated itself from this word

Curious about the term 'dord'? Here's a brief explanation:

'Dord': A Ghost Word

One common question posed to lexicographers is whether it's possible to sneak a term into the dictionary. Can you…

www.merriam-webster.com